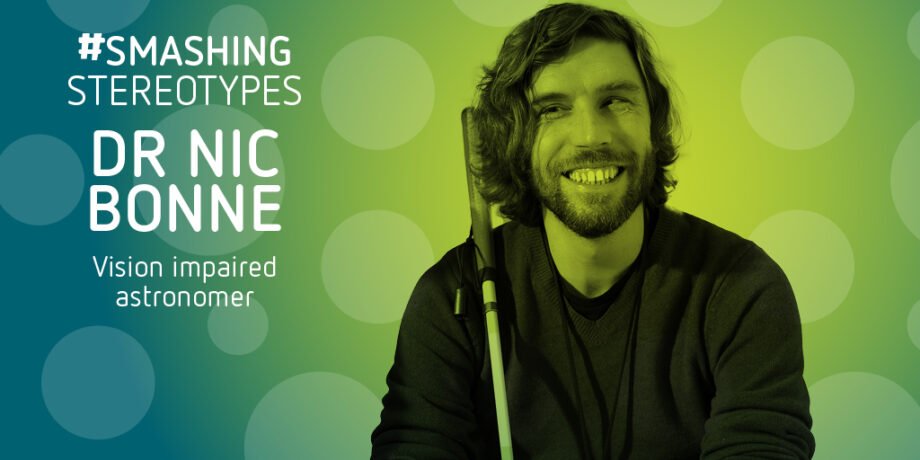

Dr Nic Bonne

Astronomer

Making space science accessible for everyone

Dr Nic Bonne is a blind astronomer dedicated to making space science accessible. Growing up stargazing in Australia, he overcame challenges to earn his PhD and now leads the Tactile Universe, creating multisensory resources for blind and visually impaired learners.

A childhood stargazing in Australia

I grew up in Bendigo, Australia, and from a really young age, my parents would take me out stargazing. We’d go out of town and find these beautiful, clear, dark night skies that you get in a lot of parts of Australia.

The problem for me, though, was that I was born registered blind. I have a tiny bit of vision, but I was born premature and placed in a humidicrib with a high-oxygen atmosphere to keep me alive. That damaged my eyes.

So, when we went stargazing, I couldn’t always see much of the night sky. But it became a shared family experience. I’d do my best to see what was up there, while my parents and brothers would describe what they could see. And that’s what first sparked my interest in space.

An early fascination for the universe

My earliest memory of being inspired by space was when I was about five. This was in the late ’80s when the Voyager space probes had just sent back stunning images of the gas giants and their moons to NASA.

I remember pressing my head right up against the TV screen to make out as much detail as possible. I was blown away by the pictures of Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, Neptune, and their moons. We had never seen anything like that before. And these were just images of our own solar system, relatively nearby, not even the distant universe.

I was especially captivated by Neptune. It was the most distant planet Voyager visited, and its deep, dark blue colour was mesmerising. The fact that I could just about make it out really captured my imagination.

From a passion to practical study

At school, I studied all the necessary subjects – lots of maths, lots of physics. I went to university and earned a degree in astronomy. Then I started my PhD and moved to Canberra, which was far from my family.

I lasted only two years. I struggled with many things I couldn’t see, but I was afraid to ask for help. Things spiralled and after two years, I quit my PhD. At that point, I thought my dream was over. I didn’t think I could become an astronomer and that I had to find something else to be passionate about.

It took another two years of talking to the right people and getting support for my mental health. Eventually, I reconnected with academics at the university where I had done my undergraduate degree. They encouraged me to come back and try again, saying they believed I could do it.

So, I returned, gave my PhD another shot, and this time, I graduated.

Never giving up on your dreams

I think it’s really important to be honest about these experiences. Not everything is straightforward. My journey certainly wasn’t, and there were clear challenges. But the second time around, I understood myself better: I knew when to ask for help and when to push through independently to gain a sense of achievement.

Thinking out of the box

A lot of the teachers, friends, and family I had growing up never said, “You’re blind, so you’re going to find this really difficult”. So, I just bumbled along, assuming everything would be OK.

Many of the people I interacted with, especially my teachers, helped me get really good at problem-solving. They saw my inability to access things as a challenge we could solve together. We often came up with weird and wonderful ways for me to do what I needed to learn or access the things I couldn’t see.

There’s always a way to access something – you just might need to get creative. That’s especially true for ‘people with disabilities or specific sensory needs.

That experience helped me develop problem-solving skills, which prepared me for a PhD. In research, you have to think outside the box and solve problems, especially in my case because astronomy is such a visual science. I always knew I’d have to tackle it differently from everyone else.

Making astronomy accessible for everyone

Most of my work now is running a project called the Tactile Universe, where we develop multisensory resources that make astronomy more accessible for people who are blind or visually impaired. We create materials that you can touch, or listen to, so that access isn’t purely visual.

It started from a chance conversation. Someone once asked me, “What would have made your PhD more accessible for you?”. My immediate response was, “If I could have touched the images rather than having to look at them, that would have made my life so much easier.”

Now we run school workshops to inspire young people and show them that STEM subjects can be accessible. We also train educators and science communicators to use our resources and develop their own accessible materials.

It’s so rewarding, using my own experiences and struggles to make astronomy more accessible for others and I hope I can inspire young people along the way.

There are still some challenges, however. I still face a lot of unconscious bias from some of the other astronomers that I come into contact with. People sometimes treat me differently because of my vision impairment.

It can sometimes be difficult to show that the work my colleagues and I are doing with multisensory stuff is actually legitimate and not just a gimmick.

The power of the right people

Based on my experiences, I believe that anybody can access STEM if they want to, but it can be difficult if they don’t have the right resources. Finding the right people, finding the right resources, and surrounding yourself with people who inspire and believe in you is crucial.

That same lecturer from my first year at university who reached out to me suggested I have another go at my PhD. She was the one who made me believe in myself again.

Nobody is ever alone. The people who support you and believe in you make all the difference.

This profile was updated on 3 March 2025.

Click here for more scientists who are Smashing Stereotypes.